What's the future of guidelines?

Better human interfaces and service- and infrastructure-oriented products

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy this post, please click the “Like” button on this email or leave a comment — this helps other people find the newsletter.

Two recent posts had me thinking over the holiday weekend about where we go with the respiratory guidelines. Morgan Cheatham laid out a futurist vision for Command Line Medicine that would enable clinicians to “direct computational processes using natural language, thereby granting superpowers and efficiencies akin to those enjoyed by software developers.” The whole thing is great, but here’s the gist:

We will exchange 4,000-click complexity and clunky Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) for conversational control of systems enabling robust data retrieval, analysis, and synthesis.

And in a post summarizing AI-enabled healthcare ideas, Nikhil Krishnan asked whether guidelines might be something that physicians could interact with via ChatGPT. As he puts it:

“The problem is that these algorithms and guidelines are published in a PDF that almost no human can easily process or keep up with, especially given they are frequently updated. So while it may be almost impossible for even a superhuman oncologist to keep up with the NCCN Guidelines…their handy AI assistant might be able to. That’s where OncoGPT comes in.”

It’s hard to look at the respiratory guidelines today and conclude they’re accomplishing their goals. They’ve tended to become the complex terrain of experts, under-serving primary care where diseases like asthma and CODP are often treated. And where they should be helping to standardize and advance medical practice, on the whole they’re doing a relatively poor job of that; in many places, we still have lots of unnecessary originality and unproductive variability in care.

There are other problems: they mostly focus on a disease in isolation rather than in context, and they don’t do much to help us measure clinical quality. Most importantly, as Nikhil notes, they can’t be updated frequently enough to keep up with the latest literature. For example, the last complete US asthma guidelines are the 2007 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. In 2020, the NAEPP finally published a brief update that covered just five selected topic areas.

As Nikhil and Morgan argue, better human interfaces to the guidelines would be helpful. Mark Levy, respiratory physician and global guideline committee member, has criticized their continuing evolution toward complexity for contributing to increasing rates of hospital admissions and preventable deaths from asthma in children in the UK. In his view, “the UK asthma guidelines while very detailed, are not user friendly. While great for academics to read about specific research findings, jobbing, busy GPs and nurses need very clear simple advice.” We might get that from the conversational interfaces of AI.

But a look at recent updates to asthma and COPD guidelines got me wondering: What if our guideline efforts were designed to shape clinical practice through technology infrastructure rather than through published reports?

This would change the guideline development process so that we don’t just get an academic report but an output meaningfully better at interacting with machines that can be directly integrated into the daily life of clinical practice.

It reminds me of this passage about The Economist from Tim O’Reilly’s book, WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

Describing his work as a senior editor at the Economist, Avent notes: “The general sense of how things work lives in the heads of long-time employees. That knowledge is absorbed by newer employees over time, through long exposure to the old habits. What our firm is, is not so much a business that produces a weekly magazine, but a way of doing things consisting of an enormous set of processes. You run that programme, and you get a weekly magazine at the end of it.” But, Avent continues, “[T]he same internal structures that make production of the print edition so magically efficient hinder our digital efforts.” And, he notes that “simply bringing in tech-savvy millennials isn’t enough to kick an organization into the digital present; the code must be rewritten.” (That is, of course, the central lesson of Amazon’s platform transformation as well.) One of the critical roles of the entrepreneur, Avent adds, is to create space for new ways of doing things.

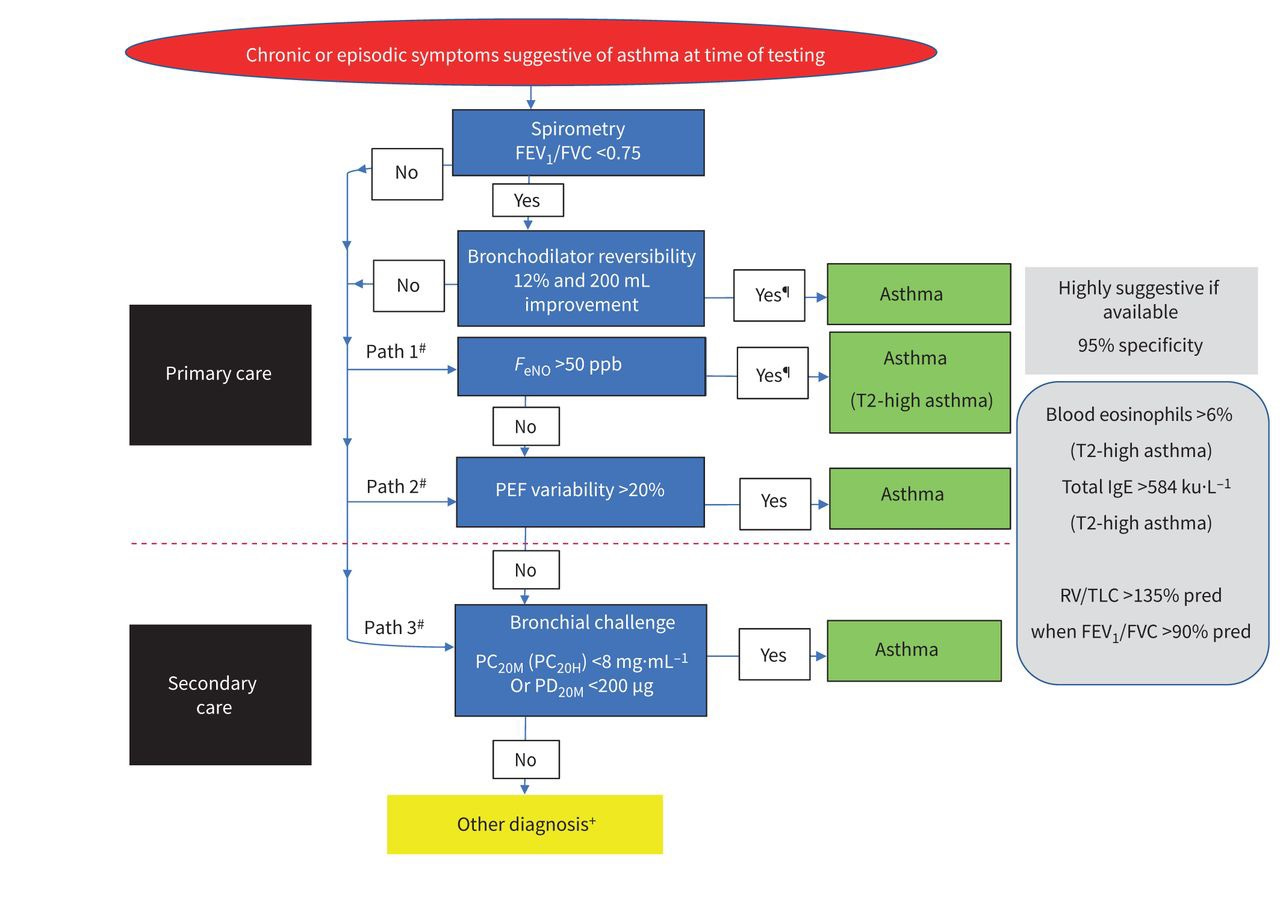

Take the process that ran recently to produce the European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in adults. A task force spent four years reviewing hundreds of new studies in an effort to improve how we identify asthma in individuals, and specifically, how an emerging array of diagnostic tests might be used to determine if someone has asthma.

The team prioritized developing "an evidence-based diagnostic algorithm, with recommendations for a pragmatic guideline for everyday practice that was directed by real-life patient experiences.” On paper, that looks a lot like a state diagram for a flow of testing and related laboratory inputs that a machine could evaluate with speed and accuracy:

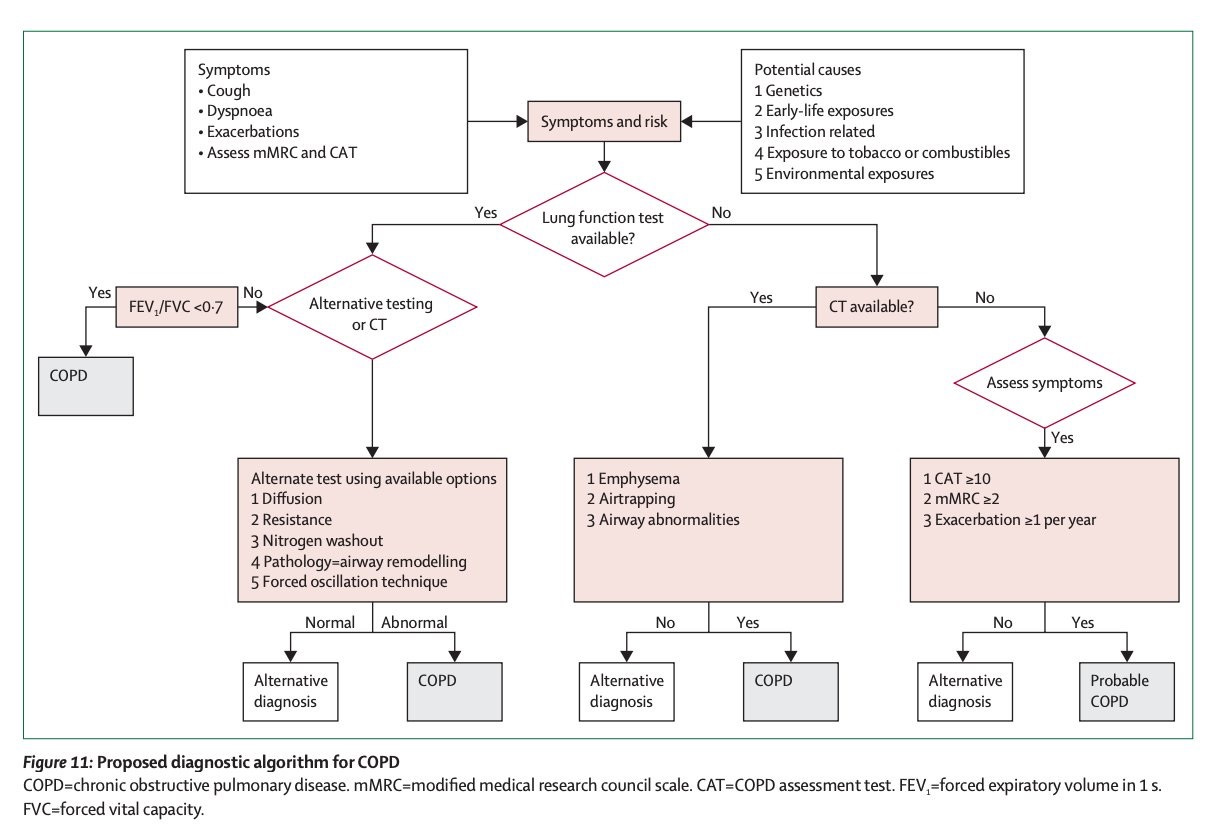

Similarly, a different global expert commission recently proposed a new approach to COPD, published in the Lancet, which presented the following algorithm to help guide the diagnosis of the disease:

The reports obviously provide a valuable and updated synthesis of expert opinion and evidence. But what we’re getting from these efforts seems incomplete and slightly anachronistic nowadays. The output feels under-optimized for its application in the modern context.

For one thing, we increasingly need these kinds of outputs to make logical sense to machines — to be readable and interpretable when integrated into other systems. When you dig in, the diagnostic algorithm for COPD is at least a little confusing or oddly presented. For example, what's going on with FEV1/FVC ratio not being immediately adjacent to lung function testing? And why isn’t there some kind of linkage from “Alternative testing or CT” to “CT available”? We need to verify and validate the logic and performance of these systems just like we do all the other components of our care and treatment.

But rather than conclude with the publication of the report, what if the professional societies took another step? What if the professional societies set out to create an endpoint or service-first version of clinical guidelines, to improve the standard of care through electronic objects and infrastructure?

We’d reform guideline committees to integrate, or pair them with, technical and informatics experts who’d help shape the development of recommendations into modern endpoints and service infrastructures that could be connected to and queried by existing clinical decision and record systems.

The guidelines would still need regular updating. But ideally that process could incrementally become more automated just as it is in software. Tests could evaluate the guidelines against newly published literature, with expert inputs, discussion, and oversight. And because their data and functionality would be exposed through service interfaces, the respiratory guidelines could also be connected to those for other diseases, so that we might start to explore and inform the management of comorbidity.

If we stop seeing published reports as the end product, one can imagine a process where we pursue a technology-first approach to guidelines that makes them a living piece of digital infrastructure serving modern medical practice. Developed and maintained by the professional societies, these versions could better accomplish the ambition and get us past some persistent shortcomings: removing unnecessary variation in care, better serving primary care, handling diseases in context, and providing paths to faster systematic updates.

Has this ever been tried? I’d love to hear your thoughts in comments or Notes

Thanks to Greg Tracy and George Su, MD for their thoughts on the topic

Hi David! Great article. You're approaching this in a very practical way. We're trying to digitize these clinical algorithms right now. Our team is building tools to digitize and map clinical guidelines in a way that can be use to transform them into care plans. Our idea is that you might 3 or 4 clinical algorithms that need to be used on a patient and you can run them all at the same time. Check us out here: https://topology.health/ it would be great to get in touch.